Sailing the Blue Skies since 2001.

Introduction

They're easy to understand, but difficult to master. Shoot-'em-ups-sometimes simply called "shooters," or abbreviated affectionately as "shmups"-are an undeniably important part of video game history. They're one of the oldest genres of the medium, and they explored groundbreaking technology. They challenged players both in the arcade and at home, and helped pave the way for the industry's success.

And yet, it's a genre that often goes overlooked. Perhaps the games are seen as too old and archaic. Maybe their straightforward gameplay leads players to think that they're boring. Some players may even simply find them too difficult. But hiding behind the deceptively basic exterior lies a rich legacy that helped shape the video game industry that we know today.

Now, on a personal note, I'm not really a hardcore fan of the genre. However, it's one that I have a lot of respect for, and I do like to play them occasionally. I wrote this article hoping to share that respect, and maybe even turn a few people on to them. This is not intended to be a comprehensive article, so if you think I've left out something important, I apologize, but don't sweat it. It's just an overview, and there are a great many more notable shmups that are worth further exploration. Also, as with many game genres, there really isn't a single accepted definition of what constitutes a shoot-'em-up. For this article, I'm simply going to use my own judgment, so if you disagree, again, don't sweat it. It's just my perspective.

At the Dawn of Computer Games...

In 1961, a student at MIT named Steve Russell came up with an idea for a new project that he and fellow members of the Tech Model Railroad Club would implement on the university's PDP-1 mainframe computer. However, this would be no ordinary computer program. Russell decided to use the $120,000 machine for a rather trivial task: playing a game.

In 1962, the game was finished. It was a simple game that involved two rockets flying around the screen trying to shoot each other. The game contained some simulated physics in the form of inertia for the rockets and a gravitational pull from a "sun" in the middle of the screen. It was strictly a two-player affair since the PDP-1 wasn't sophisticated enough to implement a computer controlled opponent. Russell named his game Spacewar.

While Spacewar was technically not the first video game ever created, it is arguably the first game in the modern sense, as we recognize them today. The simple shooting game went on to be a major influence in the development of video games over the next two decades.

In the mid 60's, a student at the University of Utah named Nolan Bushnell got hooked on Russell's creation. After graduating, he eventually decided to create a consumer version of Spacewar. He personally engineered custom hardware to run the game, and in 1971, it was released through a company called Nutting Associates under the name Computer Space. Although Computer Space flopped due to being too complex for the mainstream market, it was the very first modern video arcade game. In 1977, another version of the game, published by Cinemetronics and titled Space Wars, became the first arcade game ever to use vector graphics.

Bushnell, of course, wasn't finished with coin-operated video games. He founded the company Atari, and through it, he released his second game, Pong, based on a tennis game that Ralph Baer had implemented in his Odyssey game console. The game was a huge success, and Atari went on to be a pioneer in the home and arcade video games markets.

In 1979, the vice president of the coin-op division, Lyle Rains, came up with the idea for a game similar to Spacewar, but instead of two ships shooting at each other, only one ship would fly around the screen and shoot at rocks. Rains fleshed out his idea with programmer Ed Logg, and they ended up with Asteroids.

The gameplay was built on the same basic mechanics of Spacewar, even including a "hyperspace" button. The game was a major success, and Ed Logg went on to work on other hugely successful arcade games, including Centipede (1980), Gauntlet (1985), and San Francisco Rush: Extreme Racing (1996).

From the pet project of a group of college students to the ambitions of an entrepreneur, the video game industry had only just begun. While the arcade industry, as well as the home market, would ultimately suffer through difficult times in the mid 80's, shoot-'em-ups would go on to play a pivotal roll in its rapid development.

The Invasion Begins

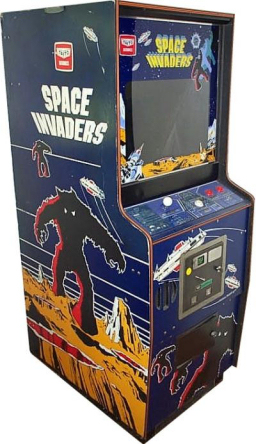

Video games were little more than a novelty up until 1978 when Japanese game company Taito reluctantly released a game called Space Invaders in Japan.

After a slow start, the game caught on a big way, with entire arcades being devoted to just that one game and eventually causing a national 100-yen coin shortage. The game was licensed to Midway for distribution in the U.S., and it instantly repeated its phenomenal success. Atari licensed the game to create its own port for the Atari VCS/2600 (the first time that had ever been done), and the console began flying off shelves.

The game could be seen as a precursor to vertically scrolling shooters, and it popularized the goal of achieving high scores. It was also the first game to feature "intermissions" between levels.

Space Invaders quickly influenced many other classic arcade games, perhaps most notably Namco's Galaxian/Galaga series. Galaxian, released in 1979, was the first arcade game ever to use full RGB color graphics.

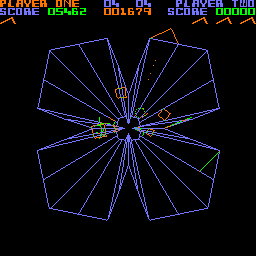

In 1981, Atari programmer Dave Theurer began work on a first-person version of Space Invaders. After a lukewarm response from other Atari employees, Theurer decided to take the game in a different direction and ended up with Tempest. Tempest was the first of a sub-genre known as "tube shooters," which could be considered a precursor to rail shooters.

Tempest presented a lot of "firsts" for video games. It was one of the first games (along with Space Duel) to use color vector graphics. It was the first to have different level layouts, rather than having one level that simply repeated over and over. It was also the first game to allow the player to choose his starting level, based on how far he got in the previous game. (In this way, it was also the first game ever to let the player "continue.")

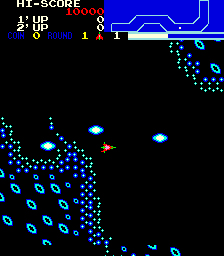

Although Space Invaders influenced many shoot-'em-ups in proceeding years, and small advancements were being made here and there, one game managed to stand out far above the rest, and set the modern template for vertically oriented shooters. In 1982, a game designer at Namco named Masanobu Endoh created the game Xevious.

Xevious was one of the first scrolling shooters, featuring varied terrain in a South American setting rather than outer space. The background wasn't just for show, either. It was used for a dual-plane combat system in which you fired standard shots at airborne enemies and dropped bombs to attack ground targets.

The graphics in Xevious were stunning for their time, being the first game to use shading techniques to give objects a 3D look. The artificial intelligence was also a major step forward, since enemies didn't simply fly mindlessly across the screen, but actively attempted to avoid the player's attacks. The game also detected the player's skill level, and adjusted its difficulty to accommodate.

Xevious contained secret items that players could discover if they fired or dropped bombs in the right spot. It also included boss fights. While both of these features are taken for granted today, they were highly innovative at the time. The game also bares the honor of being one of the first video games ever to be advertised on television.

Forming the Core

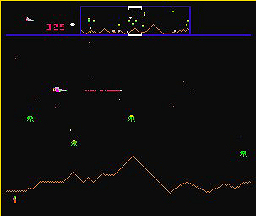

When famed game designer Eugene Jarvis joined Williams Electronics in 1980, his first project was to create a sci-fi action game with a twist. Rather than simply blasting away at aliens just for the sake of it, he would justify the aggression by providing something for the player to defend. After unsuccessful attempts at imitating Space Invaders and Asteroids, Jarvis created a play field that scrolled horizontally. Small astronauts wandered across the game's landscape, which were under constant threat from descending aliens. Thus was born Defender.

Defender still carried traces of its root material, including naming the aliens "Invaders" and having a Hyperspace button. It was also built on fairly sophisticated hardware for its time, allowing every on-screen pixel to be one of a whopping 16 colors. As one of the first games to have a play field larger than the screen, the scrolling mechanic predated even Xevious.

Despite highly complex controls and an unforgiving difficulty level, Defender has gone on to become (along with Pac-Man) one of the highest grossing video games of all time, with revenues over one billion dollars. It also spawned two arcade sequels, Stargate (later renamed Defender II for copyright reasons) in 1981, and Strike Force in 1991.

In 1981, Konami created its own simple horizontally scrolling shooter called Scramble. Unlike Defender, the screen scrolled automatically, taking the player to distinctly different levels. Because of this, it's sometimes considered to be the first "multi-level" shoot-'em-up.

That same year, a little known game company called SNK created its first major hit arcade game with Vanguard.

While it's unclear if it was released before or after Scramble, Vanguard was a very similar game. What stood out, however, is that its levels not only scrolled horizontally, but also vertically and diagonally. This was five years before Konami's Salamander implemented a similar level progression. (Vanguard also blatantly ripped-off music from the movies Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Flash Gordon.)

Both of these games served as a precursor to Konami's landmark, Gradius, released in 1985.

Just as Xevious had created the template for vertical shmups, Gradius did the same for horizontal shmups. Perhaps its most notable aspect, however, was its powerup system, which allowed players to choose which parts of their arsenal to activate next. (And as an interesting side note, the game's NES port was the origin of the most famous secret code in the history of video games: the Konami Code. It was used to instantly power up all weapons.)

Two years later in 1987, Irem released R-Type, a game that built off of, but was no less influential than, Konami's classic. The most immediately recognizable feature of R-Type was its graphics. Like other games of the time, the art direction was heavily influenced by the H.R. Giger style of the movie Aliens. The highly detailed environments and characters motivated the player to progress through the game, despite its extreme difficulty and trial-and-error style of gameplay.

Vertically and horizontally scrolling shmups formed the core of the genre, and it's often characterized by the two formats. However, as we've already seen, shoot-'em-ups can encompass a variety of styles, and many offshoots (no pun intended) have emerged over the years.

More Battle Scenes Available

"Multidirectional shooters" allow the player to shoot in any direction, as in Asteroids. A sub-genre called "arena shooters" emerged in 1980 with Berzerk. Designed by Alan McNeil, Berzerk featured a character running through a maze and shooting robots. It was one of the first games to use digitized speech. Despite the technology being enormously expensive for the time, the game's manufacturer, Stern Electronics, went all out and even created multi-lingual versions of the game.

Berzerk influenced a number of other games. Aside from a sequel in 1982 called Frenzy, it inspired a 1981 game called Castle Wolfenstein by Muse Software. Castle Wolfenstein could not only be considered the very first stealth-action game, but itself went on to inspire id Software's Wolfenstein 3D, considered the first modern first-person shooter, in 1992. Eugene Jarvis also took a cue from Berzerk and created Robotron: 2084 in 1982, which popularized the dual-joystick control scheme.

Berzerk also carries the unfortunate footnote of being the first game to be directly associated with death. Two players in the early 80's were known to have died of heart attacks mere minutes after playing the game.

Also in 1982, Sega released a shmup with an isometric perspective called Zaxxon.

It allowed freedom of movement along all three axes. While it was a hit in arcades at the time, subsequent attempts at creating shooters of this type weren't as successful. Perhaps it was because the perspective made it difficult to accurately estimate the player's on-screen position.

"Rail shooters," which give the player a 3D forward-scrolling perspective, were possibly an evolution of tube shooters like Tempest and Gyruss. Amazingly, the first game to attempt this style came out in 1983, and was yet another brainchild of Eugene Jarvis. Blaster played from a first-person perspective, and since graphical scaling technology was not yet available, the effect of objects moving towards the screen was done entirely and painstakingly by hand. Unfortunately, the game did not become a success, due in no small part to the crash of the industry that year.

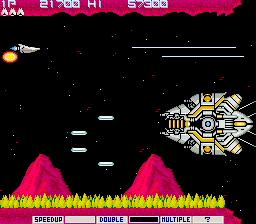

When scaling technology did become available, Sega's Yu Suzuki put it to good use in 1985's Space Harrier, as well as After Burner two years later. Both games were major successes.

Perhaps the most distinct branch of shoot-'em-ups is the "run and gun," often recognized as a genre all its own. Run-and-guns generally come in two flavors: overhead and side scrolling.

Technically, arena shooters are a type of run-and-gun, since the main character is often depicted running along the ground. The difference between an arena shooter and an overhead run-and-gun is a fine line that I don't intend to draw. But it seems to be the case that an overhead run-and-gun takes place on a playfield larger than a single screen, and it scrolls as the player moves.

Capcom's Commando, released in 1985, set the modern standards for overhead run-and-guns.

Designed by Tokuro Fujiwara, Commando had a high difficulty level and a setting based on old war movies. It was followed by two sequels: Mercs in 1990, and Wolf of the Battlefield: Commando 3 in 2008.

Sidescrolling run-and-guns are essentially a hybrid of shmups and platform games. Konami's Contra, released in 1987, was the trendsetter in this regard.

As with most arcade games from this era, it was heavily influenced by sci-fi action movies such as Predator and Aliens. Contra has continued as a series ever since.

No Refuge

After the 80's, the popularity of shmups began to wane. Perhaps advances in technology and game design changed players' tastes, and they looked forward to new ideas or more complex gameplay. Classic 2D shoot-'em-ups may have looked boring by comparison.

Regardless, shoot-'em-ups managed to survive over the next decade. Attempting to adapt to new technology and inject new ideas into the basic concept, the genre made efforts not only to satisfy fans, but also to attract new players.

In the early 90's, a British software developer named Argonaut experimented with creating true 3D polygonal graphics on the NES and SNES consoles. Not satisfied with his results, the company's founder, Jez San, received permission from Nintendo to develop custom hardware that could be implemented within the game cartridge itself. The result was the Super FX microchip, recognized as the world's first 3D graphics accelerator.

Under the supervision of Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto, Argonaut's demos were transformed into a rail shooter called Star Fox, released on the SNES in 1993.

It was the first fully 3D, polygon-based game ever made for a home console, and it predated the first 32-bit console, the 3DO Multiplayer, by several months.

Also in 1993, a Japanese developer known for its 2D shoot-'em-ups called Toaplan took a different approach. Keeping their designs in two dimensions, they created a game with hundreds of moving objects on screen at once. The result was Batsugun, which is often considered to be the first in a hardcore sub-genre known as "manic shooters" or "bullet hell shooters."

Manic shooters are characterized not only in the number of bullets on-screen at once, but also in their behavior, often forming complex patterns or mazes that the player must precisely maneuver his/her character through. This is balanced by giving the player a wide margin of error in the form of a small "hit box," which makes it easier to squeeze through tight spaces.

Treasure, an independent developer known for creating games around innovative gimmicks, made its first straightforward shmup with Radiant Silvergun, released into Japanese arcades in 1998.

Among its notable features are its unique weapon system, level progression, and a scoring method known as "chaining." By shooting three enemies of the same color in a row, the player earned score multipliers. It all added up to what many consider to be one of the greatest shoot-'em-ups of all time. Yet ironically, the game received only one home console port to the Sega Saturn, and neither version was released outside of Japan.

Treasure followed up Radiant Silvergun in 2001 with a spiritual sequel, Ikaruga. Ikaruga explored the idea of chaining even further with a polarity system that allowed the player to change the color of his/her ship and bullets. This allowed the player to absorb enemy bullets of the same color. The game was designed so intensely around this concept that some people think it feels less like a shooter and more like a puzzle game. Ikaruga managed to see an international release through its port to the Gamecube in 2003. Alongside its predecessor, it's considered among the best of its genre.

None of this was enough to re-ignite widespread interest in shoot-'em-ups, however. Without hope of mainstream success, the few developers that still created 2D shmups aimed them directly at the niche market, which only served to alienate the mainstream even more.

Sequels to popular longtime franchises were few and far between, and the ones that did emerge were often considered sub-par. Some franchises were even ended entirely, as Irem did in 2003 with R-Type Final.

The classic 2D shoot-'em-up, which was so popular and pioneering in the early years of the industry, seemed destined for obscurity.

The Legacy Continues

Online console gaming had been little more than a novelty until Microsoft introduced the Xbox Live service for its Xbox console in November 2002. A year later, they added a service called Xbox Live Arcade that allowed players to purchase and download games online. This form of digital distribution would become extremely important for the future of shoot-'em-ups.

Born out of an unlockable minigame in Bizarre Creations' Project Gotham Racing 2, Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved was one of the first games available for Microsoft's new service in November 2003.

It was a basic multidirectional shooter that had the look and feel of an early arcade game, featuring vector-style wire-frame graphics reminiscent of Asteroids and Tempest. The gameplay featured dual-joystick control, like Robotron: 2084. The simple, yet addictive challenge of achieving a high score quickly made it the most downloaded game on the service.

It was so popular that a retail version was eventually created for the Wii and DS systems in 2007 called Geometry Wars: Galaxies; and a sequel, Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved 2, was released on Xbox Live Arcade in 2008.

The game was part of a retro gaming revival that was popularized through digital distribution, and with it, shooters were regaining some attention from the mainstream audience. Many classics were being rediscovered through Xbox Live Arcade, as well as Nintendo's Wii Virtual Console. Brand new games were also produced, such as Everyday Shooter on Sony's PlayStation Network. New retail games also continued to appear, such as Blast Works: Build, Trade, Destroy for the Wii.

Not to be forgotten, many classic franchises were revived through sequels and remakes. Konami returned to the Gradius series in 2004 with the Treasure developed Gradius V, arguably the best in the series. Both Taito's Space Invaders and Namco's Galaga returned in 2008 with Space Invaders Extreme for the Nintendo DS and Sony PSP, and Galaga Legions on Xbox Live Arcade.

Just like in the games themselves, the shoot-'em-up genre managed to maneuver through overwhelming resistance and emerge on the other side unscathed. After helping to birth an industry, they pushed it to its greatest heights. From catering to the hardcore, they returned to their roots and reminded everyone what made them great to begin with. While they may never achieve the same levels of success they once enjoyed, shoot-'em-ups are an enduring thread through the history of video games that are sure to be around for a long time to come.

Sources:

The Ultimate History of Video Games (Steven L. Kent, Three Rivers Press, 2001)